During my seventeen years as a member of Oberlin College’s German and Russian Department, I had the opportunity to interact in various ways with twelve Max Kade German writers-in-residence who came from West and East Germany, Austria and Switzerland. Before joining the Oberlin faculty in September 1969, at age twenty-six, I had never interacted with a writer, not even briefly. Most of my course work and research in graduate school brought me into contact with German-language writers who for the most part were no longer living. We used secondary literature and various critical approaches to gain insight into their works and thought processes. As graduate students we were taught how to do this by our professors, who were supposed to be experts in literary analysis. As I marched on in Middlebury College’s MA program and Johns Hopkins University’s PhD program, I felt confident that the second-hand information I was absorbing on German-language writers of the twentieth and earlier centuries was correct. But later on, my interactivity with living writers who had residencies at Oberlin College would lead me to doubt the accuracy of what I had learned as a student about individual authors and fuel my desire to begin working on contemporary German-language writers.

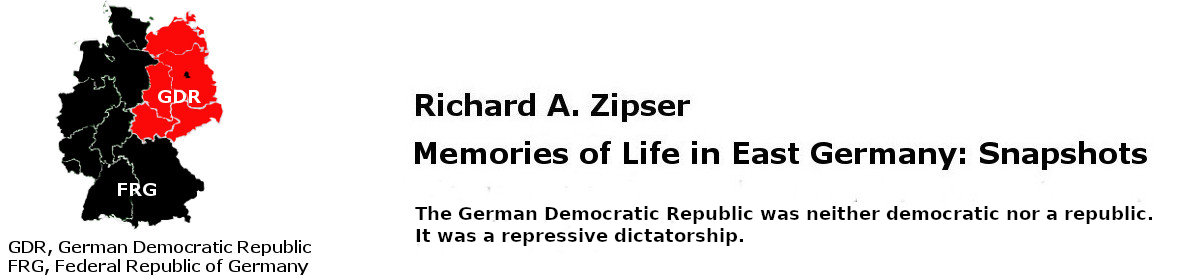

Interacting at Oberlin College with writers from different German-speaking countries was immensely rewarding, on a personal as well as a professional level. Without exaggerating, I can say that it quickly opened up a new world to me that both complemented and augmented the book knowledge I had accumulated as a student at several other colleges and universities. Six of the writers-in-residence I experienced at Oberlin came from communist East Germany (officially known as the German Democratic Republic): Christa Wolf (1974), who was accompanied by her husband Gerhard Wolf, a highly-regarded editor, publisher, literary critic, and author; Ulrich Plenzdorf (1975), whose wife Helga accompanied him; Jurek Becker (1978); Bernd Jentzsch (1982); and Karl-Heinz Jakobs. During their residencies in Oberlin, I developed a friendship with the Wolfs and Plenzdorfs, whom I had been instrumental in bringing to the College. Under their influence and with their guidance, my nascent interest in the literature of East Germany blossomed rapidly. They helped me conceptualize a research project for my first sabbatical leave in 1975-1976, which would usher me at full speed into an exciting new field of specialization—contemporary GDR literature. Moreover, the project we co-designed would lead to many direct contacts and enriching experiences with GDR writers, encounters that would prove invaluable to me in both the short and the long run. This marked the beginning of an important change in direction in my focus and evolution as a Germanist, a process I have discussed at length in the snapshot entitled Leap of Faith. (This text is located in the online version of Memories of Life in East Germany: Snapshots, within the grouping labeled “Assorted Memories.”) See https://www.richardzipser.com

At Oberlin College especially, I had close contact not only with the six East German authors mentioned above, but with several others who spent a good portion of the spring semester as our guest writers. The first ones I got to know well were prominent writers: Tankred Dorst (1970), Christoph Meckel (1971), and Peter Bichsel (1972). In my first year on the Oberlin faculty, my department chair gave me a special service assignment. I was tasked with looking after prizewinning playwright, filmmaker, and storyteller Tankred Dorst during his three-month stay. This involved driving Tankred here and there, e.g., to Johnny’s Carryout and Wine Shop located just outside the city limits, since Oberlin was a “dry town”; also, helping him with things like opening a bank account and getting a library card. As I cheerfully performed these duties, I gradually became acquainted with Tankred as a person, rather than as a celebrity writer, and over time we became friends. My most important task was to translate the public lecture he was going to deliver in April from German into English. He wrote the lecture while in Oberlin and gave me the text a page or two at a time. When he and I had finished working on it, we practiced reading it several times since Tankred did not speak English very well. To improve his English and deepen his understanding of our society, he embarked on an ambitious program of reading classic American authors, with a dictionary at his side. From reading works by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, Thomas Wolfe, and William Faulkner, he learned a lot about nineteenth- and twentieth-century America. I admired his purposefulness and desire to make the most of his Oberlin stay in various ways. Tankred, like all of our visiting writers, was welcome to have lunch and dinner at no cost in the German House dining room. This was one of the ways we encouraged our visiting writers to interact with students in the German program. My wife and I lived about two blocks away from Tankred in Oberlin, where he was renting the house of a professor on sabbatical leave. We invited Tankred to join us for dinner about twice a week and occasionally on weekends as well. We had no difficulty finding conversation topics of mutual interest, so I always looked forward to his evening visits. With each passing week, I felt more and more comfortable interacting with Tankred and looked forward to the special event at which he would give his lecture on “The End of Playwriting.” Since I had translated everything into English and prepared Tankred to read it smoothly, I felt like I was also participating actively in the event. The showcasing of Tankred, attended by many Oberlin students and faculty, persons from the town’s German-speaking community, as well as guests from several colleges and universities in the region, was a great success. Tankred was pleased and relieved, as the preparation for the big day had been stressful for him—and for me as well. Not only did he thank me warmly, he also gave me permission to publish the translated version of his talk. I offered it to The Antioch Review, one of the top literary magazines in America, and they were delighted to publish it (see Vol. 31, No. 2, 1971, 255-266). This was my very first publication and I was of course delighted to see my translation and name in print! After leaving Oberlin, Tankred embarked on a multi-university lecture tour around the country. In addition to reading from his works, he gave a talk in English at each university on “The End of Playwriting.” One final comment on the very first Max Kade German writer-in-residence I experienced: Already internationally famous before coming to Oberlin, Tankred Dorst would later on in his very prolific career be widely hailed as the doyen of contemporary German playwrights.

In addition to the nine writers mentioned above, other authors I got to know well via Oberlin’s guest writer program and liked very much were Barbara Frischmuth (1976), Max von der Grün (1977), and Peter Rosei (1983). From 1975 on, my work on several East German literature projects brought me into contact with more than fifty writers in East Germany. The ones I got to know well and befriended were (in alphabetical order) Heinz Czechowski, Gabriele Eckart, Elke Erb, Stefan Heym, Sarah Kirsch, Günter Kunert, Klaus Schlesinger, Helga Schütz, Martin Stade, and Bettina Wegner.

Befriending writers, as I was able and fortunate enough to do many times, can have a drawback, as I would learn in the late 1970s. I want to elaborate on this topic, which I am calling “too close for comfort.” In the 1970s and 1980s, the two GDR writers I got to know best and regarded as close friends were Ulrich Plenzdorf and Jurek Becker. I also had a warm personal relationship with Sarah Kirsch and Christa Wolf. If I reveal that these four persons are my favorite East German writers, that will not surprise anyone who has read my memoirs, Remembering East Germany. From Oberlin to East Berlin (2021) and Memories of Life in East Germany: Snapshots (2022).

***************

In December 1977, toward the end of my two-month stay in East Berlin, I attended a farewell party for prose writer Hans Joachim Schädlich, who was being forced by the GDR authorities to leave East Germany permanently. Expatriation was his punishment for the unauthorized publication in West Germany of a controversial book of short prose, Versuchte Nähe (Attempted Closeness). The party was held in the spacious, centrally located Berlin apartment of songwriter-singer Bettina Wegner and prose writer Klaus Schlesinger, who had invited many writers and journalists, including several from the West. Here I met Heinz Ludwig Arnold, a well-known West German literary journalist and publisher who was editor-in-chief of TEXT+KRITIK, a quarterly literary journal he had founded in 1963. Arnold took an immediate interest in my work on contemporary GDR writers and invited me to submit a proposal for a monograph on Ulrich Plenzdorf or Jurek Becker for publication in TEXT+KRITIK. This highly-regarded journal was producing four monographs each year, focusing primarily on contemporary German-language writers and literary topics of general interest. As a young professor, I was flattered by his invitation and eager to accept it, but should my monograph be on Becker or Plenzdorf? Arnold left the choice up to me and, after thinking it over, I decided to go with Becker. The fact that Becker would be coming to Oberlin for most of the spring 1978 semester made my decision an easy one. Apart from a monograph on Christa Wolf in January 1975 and one on Volker Braun in July 1977, Arnold’s journal had published very little on East German literature. He was eager to add more GDR authors to his roster and I was prepared to help him.

Jurek Becker arrived in Oberlin in mid-February 1978. Understandably, I was very excited about his visit, since we had become friends in East Berlin and I had already spent a lot of time in his company, well before his trip to America. This distinguished him from the GDR writers I befriended while they were staying in Oberlin. As Jurek was getting settled in a small apartment in a dormitory and in a faculty office in Rice Hall, I had several things to do in connection with his stay. As quickly as possible, I needed to compose the text for a flier announcing his visit that would be distributed throughout the College. The flier would have a photo of Jurek, some biographical information, and a brief commentary on each of the four novels he had published during the previous decade. I had composed similar fliers for some predecessors of Jurek, and I looked forward to preparing the one that would introduce him to the Oberlin community and other parties.

While Becker at first relished the fame that followed the publication of his first novel, Jakob der Lügner (Jacob the Liar, 1969), later on he struggled to escape from its mantle. It was his undeniable good fortune to have written his most successful book at the outset of his career, but he considered it something of a curse. Jurek always wanted to discuss the latest book he was working on, not something he had published at an earlier point in time, and especially not his story about Jacob which is in my view the most powerful Holocaust work in existence. Jurek told me this and much more while we were having a bite to eat and a few beers at a local Italian restaurant. We had gone there so that I could ask him some questions about the four novels he had published and some other things related to his writing, in preparation for writing the flier. Jurek, who really disliked answering literature professors’ questions about his writing and intent as an author, was eager to be helpful on this occasion. He and I both wanted to create a flier that would impact readers in a very positive way and generate considerable interest in our visiting writer. With this goal in mind, I had prepared a list of questions that I hoped would yield some fresh insights into the nature and purpose of his novels.

We started the Q&A session with Jacob the Liar. It is the story of Jacob Heym, a middle-aged Jew in a Polish ghetto during the German occupation, who is forced by fate and circumstances to become a “liar.” Hope is Becker’s theme, and his novel shows that it is not necessarily a positive force in the lives of persons who are trapped in a hopeless situation. Jurek and I then moved on to his second novel, Irreführung der Behörden (Misleading the Authorities, 1973). Here Jurek depicts the career of an opportunistic young writer, Gregor Bienek, who makes certain compromises and concessions as an artist in order to become successful. Less concerned with how somebody becomes or has become an opportunist, the author examines how somebody lives with the knowledge that he is an opportunist. “One can surely live as an opportunist,” Becker maintains, “the question is only whether or not one can remain a writer.” Der Boxer (The Boxer, 1975), described by the author as “an attempt to translate my father into literature,” is the most autobiographical of Becker’s first four novels. It is the story of Aron Blank, a survivor of the concentration camp living in post-war Germany, and his unsuccessful struggle to overcome isolation and liberate himself from the past. With reference to his novel’s theme, Becker told me: “I am interested in the question of whether or not there are persons in society who, because they have suffered so much, have a special right to tolerance. I think there are. And I am also interested in the question of whether or not this right to tolerance is the same as the right not to be criticized. I think not.” Schlaflose Tage (Sleepless Days) is the title of the novel Becker published in February 1978, just before arriving in Oberlin. The rejection of this book for publication in East Germany was a major factor in its author’s decision to leave his country for an indefinite period of time. The main character in the book is a school teacher, Karl Simrock, who quite suddenly comes to the conclusion that he has been leading a false existence. At age thirty-six, he finally realizes that his job as a teacher never was to educate children, but merely to communicate to them instructions received from higher authorities. His determination to rectify this situation, to stop existing as an opportunist, leads him to make major changes in his professional and family life. As a result, he loses his job and the comfortable bourgeois existence that went along with it, but is still happier than he had been with himself and his previous life.

After I finished jotting down Jurek’s responses to my questions, we chatted for a while before heading back to the college campus. At one point, I mentioned that Heinz Ludwig Arnold had invited me to write a monograph on a GDR author for publication in his TEXT+KRITIK series, and I had decided to write a book focusing on him. What prompted me to choose him as the subject of my monograph, Jurek wondered. There were several factors that led to my decision, I replied. The most important one was this: I admired him not only as a writer and storyteller but as a person of principle, an attribute that is reflected in each of his novels. Also, because of our friendship and the amount of time I had spent in his company since November 1975, I had gotten to know him well as a person. Furthermore, I explained, my unique extensive access to prose writer Jurek Becker had enabled me to gain insights into his works of fiction that were original and important. I was eager to publish and thereby share this information with other interested parties.

Jurek was intrigued and asked me to give him a couple examples of my new insights. “Well,” I said, “I think I’ve come to understand why nature does not play much of a role in your narratives. There are no descriptions of mountains, hills, valleys, or other landforms; nor of water bodies such as rivers, lakes, ponds and the sea; and there is no mention of forests and trees, gardens, shrubs and plants. What is not present by way of living creatures from the animal kingdom and living elements of land cover is significant, I think, and right now I’m in a good position to explain it.” Moving on, I asserted: “Let me give you another example. In your novels, the protagonists are all men, and I think I have figured out the reason for this. There are no strong female characters in your books. Women are present, to be sure, but they do not have important roles to play. For the most part, they are minor characters and are confined to the background. This, like the very limited presence of non-human elements of the natural world, is an important aspect of your writing that needs to be explored and explained, and I’m prepared to do that in my monograph. Jurek, who had been listening intently, his face expressionless, had something to say at this point, something I will never forget. He looked at me from the other side of the table and in a friendly voice said this: “Dick, don’t write that book, otherwise we won’t be friends anymore.”

My meeting with Jurek turned out to be instructive in a way I could not have anticipated. The main takeaway for me was to be exceedingly cautious and circumspect when using information about a writer that has been gathered within the private domain. While writers are public figures, they certainly have a right to privacy, and one should not exploit the advantages and privileges that frequently accompany friendships with famous persons. In a single sentence Jurek had delivered that important, immensely helpful message; it prevented me from misusing some information I had gathered through direct observation or by other informal means. As a result, I did not write the monograph on him, nor did I write one on Ulrich Plenzdorf, the other celebrity writer I had befriended in Oberlin and Berlin. I realized that I had gotten too close to both of them for comfort—for their comfort and for mine!