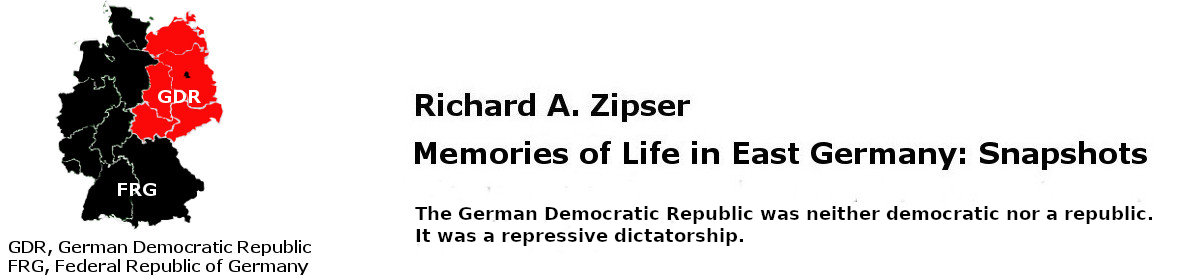

My interest in GDR literature was awakened in the spring of 1974, when prominent East German prose writer Christa Wolf spent six weeks in Oberlin as German Writer-in-Residence. She was accompanied by her husband Gerhard, a well-known literary scholar and editor with connections to many contemporary GDR authors and publishers. I spent a lot of time with the Wolfs while they were in Oberlin, and they introduced me to the GDR literary scene through carefully selected readings and instructive conversations that were truly fascinating. When I told the Wolfs that I would be taking a one-year sabbatical leave in 1975-1976, they encouraged me to think about doing a project on GDR writing in the 1970s and promised to assist me. During the course of our discussions, the outline of a possible project gradually emerged. The focus would be on new directions and trends in East German literature during the period of “thaw” that occurred shortly after Erich Honecker replaced Walter Ulbricht as leader of the Socialist Unity Party in 1971. Another prominent East German author—Ulrich Plenzdorf—came to Oberlin as writer-in-residence in the spring of 1975. Plenzdorf and I became good friends that semester, and he too helped me shape and finalize plans for my first sabbatical leave, a good portion of which I intended to spend in the GDR.

Christa Wolf, the seventh Max Kade German Writer-in-Residence at Oberlin College differed in several ways from her predecessors. She was the first novelist, while those who came before her were lyric poets, playwrights, and short-story writers. Also, as the first East German writer to visit Oberlin, she was able to give our community valuable insight into that other, very different, German culture. Finally, she was not only one of the first two women writers in residence (the first being Helga Novak in 1973), but also the first to integrate the sexes by bringing her spouse with her.

Born in 1929 in Landsberg an der Warthe (former German territory, located in western Poland today), about one hundred miles east of Berlin, she spent her childhood years under Hitler and in time of war. After WW II ended in 1945, she worked for a few years as the secretary to the mayor of a village in Mecklenburg. In 1949 she began studying literature, first at the University of Jena, then at the University of Leipzig, receiving her diploma in 1953. She then became an editor for the magazine Neue Deutsche Literatur (New German Literature) and for Neues Leben (New Life), a publisher of books for children and young adults. Later she worked as an editor for the Mitteldeutscher Verlag (Mid-German Publishing House) in Halle, which published her Moskauer Novelle (Moscow Story) in 1961. For this first work she received the prize of the city of Halle, and for her next prose work, Der geteilte Himmel (Divided Heaven, 1963), both the Heinrich Mann Prize and the national prize of the GDR. Her third book, Nachdenken über Christa T. (The Quest for Christa T., 1968), became a bestseller in its West German original and paperback editions. When this novel was first published in East Germany, it immediately created a storm. GDR authorities instructed book dealers in East Berlin to sell it only to well-known customers who were engaged professionally in literary matters. Also, the novel was severely attacked at the 1968 meeting of the East German Writers Congress, and it was condemned by government officials who eventually banned it, even though it has nothing explicit to say about politics in the GDR. But those of us who are able to read between the lines will easily see why Christa Wolf’s Christa T., the novel, its main character, and its author stirred up SED Party leaders and made them apprehensive. On the surface it is a straightforward story of the unremarkable life of an introspective young woman growing up in Nazi Germany, then dying at age thirty-one in Communist East Germany. Beneath the surface it is a first-hand, subjective account of everyday life in a repressive society that does not tolerate persons who question socialist beliefs and the way of living in a socialist state that expects all its citizens to conform. Christa T. is shown to be a victim of this restrictive society.

All three of Christa Wolf’s major early works are concerned with the inner development of their central character. In all three, a heroine searches with increasing awareness to find herself. The search, not so much for self as for the right way in life, is at the same time a search for truth. In each instance the reconstruction of the past, even one’s own past, gives rise to the question that concerns so many novelists: What really happened? Thus William Faulkner shows the hero in Absalom, Absalom! setting out to learn from the protagonists about what had happened in their lives and what to them was the meaning of the past. Similarly, the heroine of Moscow Story, a young doctor on a trip with a professional group to Russia, again meets the Russian whom she knew eight years earlier as an enemy officer in her German village after the war. Only after making clear to themselves and each other the love and hostility each felt back then for the other are they able to resume with new strength the useful lives they have made for themselves in their own countries.

The decision about which life (communism vs. capitalism) and which country (East vs. West Germany) is more difficult for the heroine of Divided Heaven, Rita. This is a very romantic and sad story, which takes place at the time the Wall was built. Here, too, the past—the Nazi years as well as the early years of the GDR—is reconstructed through conversations with many of the novel’s characters. The gradual recreation of Rita’s past reveals to the reader that it is because of her love for a young chemist, Manfred, that she has left her village and secretarial job to join him in Berlin where she will study to become a teacher. Rita is required to work in a factory during her student years and becomes increasingly involved in the affairs of her workplace. In the process, she comes to identify with the socialist aims of her country and the factory workers. This leads to conflict with her lover Manfred, whose dishonest father is guilty of wrongdoing while managing the factory. Despite his hostility toward his father and mother, who had both collaborated with the Nazis, Manfred asserts his bourgeois heritage and leaves for the West where he believes he can better fulfill his goals as a scientist. Rita remains behind to lead the more difficult but useful life in the East, thereby choosing to sacrifice her personal love and asserting her commitment to a new, progressive society.

Christa Wolf’s third novel, The Quest for Christa T., is the most controversial of all with its insistence on finding oneself while at the same time serving society. The coincidence of both author’s and heroine’s first names points to the autobiographical component in the novel. Christa Wolf’s teacher of German literature at the University of Leipzig, Professor Hans Mayer, attests to the existence of a student there whose life closely paralleled the heroine’s; he also recalls Christa Wolf’s own examination essay on the same topic as the heroine’s. Clearly then, though Wolf’s heroine is a composite of fact and fiction, much in her crises of conscience is real and part of Wolf’s own experience. The author’s insistence on the search for truth and the discovery of it in this novel goes hand in hand with her ongoing search for new ways of writing. Here she makes use of entirely new narrative techniques, which represent a radical departure from the prescribed principles of socialist realism, the officially sanctioned style of writing in the GDR during the 1950s and 1960s. The narrative structure of The Quest for Christa T., described by some critics as an interweaving or merging of narrative voices, provides a marvelous example of the “subjective authenticity” that is a distinctive characteristic of Wolf’s style. For further information on her literary style and her observations on the function of literature in East and West German societies, see Reading and Writing (Lesen und Schreiben), a collection of essays she published shortly before coming to Oberlin, Ohio (Darmstadt: Luchterhand, 1972. 220 pp.).

The time has come to report on Christa Wolf’s activities while she was in Ohio from April 3 until May 12, 1974. I have elected to let Christa tell the story in her own words, which she fortunately did in an essay she wrote in July 2003. The essay represents her contribution to a volume chronicling Oberlin College’s German writers-in-residence program from 1968 to 2003 (Welcome and Departure [Willkommen und Abschied)]. Thirty-Five Years of German Writers-in-Residence at Oberlin College, ed. Dorothea Kaufmann and Heidi Thomann Tewarson. Rochester: Camden House, 2005. 398 pp.). My translation of her essay, which is located on pp. 55-58 of the book cited above, appears below.

Writer-in-Residence in Oberlin, 1974

When we, my husband Gerhard Wolf and I, arrived in Oberlin, Ohio on April 3, 1974, we had never before set foot on American soil; we didn’t know the meaning of the term “Midwestern,” nor did we know what a “dry town” was, nor how to behave if there is a tornado. So the next day, blissfully trusting Richard Zipser from the German Department, we drove out into the countryside in order to buy beverages outside the city limits that were not available in the puritanical “dry” town, this even though a banner with a tornado warning was showing continually on our television set and outside the wind was blowing pretty hard. Back in those days, there were wines available in the USA with bright labels that stated “like Liebfraumilch,” which were—and I am expressing myself politely—disappointing. (Not only that—the entire gastronomic culture has in the meantime improved immensely!) But the gusts of wind quickly developed into a storm and, as we once again sat happily watching television in the evening, we were shown that a small nearby settlement made up of wooden houses similar to those in Oberlin had for the most part been blown away.

The same thing—almost the same thing—was bestowed upon us as we were about to depart. On May 11, as we were gathered at our farewell party and waiting for the steaks to finish grilling, the radio again broadcasted a tornado warning for Oberlin. This time we went into the so-called “tornado cellar” in the neighbors’ house—nothing more than a corner of the cellar that was reinforced with crossbeams and sturdier materials, which measured by our European standards would be blown away by any gust of air. There we stood, along with well-dressed members of another party, holding cocktail glasses as we heard on the radio that the tornado had caused serious damage on Cedar Street. But that’s where we are living!, we cried out. Our friends calmed us down though, saying: Cedar Street is long. After midnight, however, as we approached our house—which actually belonged to Professor Kurtz who had rented it to us while he was on vacation—the area right in front of this house was bathed in bright light; a huge municipal repair vehicle was blocking the street, and workers in orange-colored overalls were busy cutting up the large tree that at this very spot, together with its entire root system, had been twisted out of the earth and tossed onto the street. There was an electrical power outage; our neighbors were worried about the turkeys in their deep freezers and offered us emergency aid—just as a couple of students had stopped by our place at the beginning of our stay with homebaked bread: We Europeans would surely have our issues with the American white bread . . .

Indeed, and these issues persisted; all the same I gradually learned to find those grocery items at Fisher’s that appealed more to our taste, yet there was one more crisis when Gerhard came down with a serious stomach ailment and was supposed to eat oatmeal, which was only available in various “flavors,” the scent of which had caused him to develop an allergic reaction, until I discovered—after numerous failed experiments—“Quaker’s unflavored oatmeal.”

So much for “culture shock.” Or, perhaps a couple more additions after all. Whenever we ventured to take a walk, after just a few hundred meters a car would inevitably pull up beside us and a friendly driver would ask if our car had broken down and if he could take us somewhere. In the supermarket a black employee would pack my purchases in the famous paper bags, and then his jaw would drop with regularity when outside he had to place the bag in the basket of a rusted bicycle I had borrowed and which responded to the name “Horatio,” rather than in the trunk of a fancy automobile. In the school bus driving by the white children were sitting up front, the black ones together in the back in a tightly knit group; in the school I visited one time they were seated the same way in separate groups in the classroom. And when the teacher asked a sixteen-year-old girl after class: What do you know about the GDR?, a one-word response came after a long pause for thought: The wall.

Now this was the other side of the culture shock that we may have inflicted on our American partners: We came from a country, the existence of which was unknown to the female and male students from the farms in the Midwest, and the literature of which they had heard nothing about previously. We were prepared for that and had sent diverse packages with books in advance, the foundation of a small GDR library. Hence we offered colloquia in which names like Anna Seghers cropped up, but we focused chiefly on the “middle” and younger generations of authors: Erwin Strittmatter, Hermann Kant, Volker Braun, Johannes Bobrowski, Karl Mickel, Ulrich Plenzdorf, Günter de Bruyn, Irmtraud Morgner, Brigitte Reimann, Sarah Kirsch, Rainer Kirsch, Reiner Kunze, Uwe Gressmann. I took on the prose writers, Gerhard the lyric poets. Once a week we hosted a wine and snacks gathering at home for persons interested in readings and discussions that frequently proceeded along these lines: It’s like this where we live, how is it where you live?

On our free evenings we sat in front of the television and watched, somewhat stunned, as the stack of tape cassettes beside President Richard Nixon’s chair—the “tapes” he had to hand over—grew higher and higher and convicted him of having illegally wiretapped his opponents during the election battle. Then I would sit at Professor Kurtz’s desk, work for a while on Patterns of Childhood (Kindheitsmuster, published in 1976) or read Doctor Faustus by Thomas Mann from the professor’s library. Breathing all around me was that perfect American house, with its umpteen bedrooms and just as many bathrooms, that got warm and cold automatically (we were experiencing cold weather, even snow) and that devoured kitchen garbage amidst irritating gargling sounds in the drain. Was that the future? Or was the future the doctor who refused to have Gerd admitted to the hospital, in order to diagnose the cause of his medical condition: “It’s very expensive, madam!” Or the family of the truck driver with whom he eventually shared a room, who—as soon as they had greeted the husband and father—would gather around his bed and stare intently at one of the two televisions that were hanging from the ceiling? We could not get this man to turn off the television, not even once: “After all, he has paid for it!”

Max Frisch called one evening from his hotel room in New York, 5th Avenue, and berated me because the GDR had planted a spy on Willy Brandt’s staff, which brought about his resignation. He had been drinking a lot of whiskey, and so had I. In the end, we became reconciled by way of shared outrage.

We acquired friends. We marveled at the College’s music hall and its well-endowed art museum. When we went for a walk on the campus, we could tell if older married couples were European immigrants by the way they walked. I had to deliver a lecture in English: “Prose writing today,” which I wrote in German, had Dick Zipser translate, and then rehearsed for days. In the early morning I went swimming in the indoor pool; at midday or in the evening we frequently would go to the German House and dine there. I attended a lecture on the Shakers and responded to questions by a women’s group about the emancipation of women in the GDR. I was not certain that we had the same understanding of emancipation, but it was clear that we were interested in one another. I knew that this interest would stay with me.

On May 12, we flew from Cleveland to New York, on May 13 from New York to Prague; there we were already as good as home.

July 2003

I could write much more about Christa Wolf, who was a central figure in East German literature and politics during the 1970s and 1980s. However, my focus here is on the time she spent at Oberlin College, where I first met and got to know her and her husband Gerhard in 1974. During the later 1970s, I visited her a few times at her home in Kleinmachnow and, after she and Gerhard moved to Berlin’s central district (Mitte), in her Friedrichstrasse apartment on numerous occasions. In those and later years, she wrote many more important prose works that enhanced her reputation significantly and perhaps should have paved the way to a Nobel Prize. But that did not happen, unfortunately in my view, possibly because of her brief collaboration with the Stasi as an informant in the early stages of her career as a writer. After the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the GDR state, Christa Wolf continued to write and publish in post-unification Germany until her death in December 2011, and would eventually become one of the most celebrated German authors of the twentieth century. In 2002, she was awarded the first German Book Prize for her lifetime achievement. The jury lauded her for “courageously confronting the great debates of the GDR and reunified Germany.” In closing, let me say how pleased I am to have known Christa Wolf personally and how immensely grateful I am for the assistance and guidance she and her husband gave me in the 1970s. Without their help I never would have been able to carry out my first major book project on GDR literature and most of the GDR-related book projects in the years that followed.

|

|